Part 2: Solution Design — Design Process of Modern IT Systems and Large Software Integration Projects

1. Overview

From the 1970s onward, IT software projects acquired a notorious complexity due to the advancement of hardware (exponential rise in processing power of the personal computer) and software technologies (proliferation of programming languages and frameworks).

These advancements captivated users and radically changed their preferences, leaning ever more towards modernization and digitalization.

Today, and more than ever, digitalization has pervaded our lives, and software exists for almost everything.

Standalone solutions or products are now scarce, and the integration of mature technology and platforms in large IT systems allows businesses to offer rich, seamless, end-to-end services.

As project size spiralled upwards due to adding more platforms to the standard offering, careful project planning and solution design became critical to lowering project risk to a comfortable level so that it could be carried over during execution.

Agile design and its tendency to bypass top-down, overarching plans favouring small incremental modifications and faster releases were much too dangerous as the cost of change in large projects soared. Much forethought had to be placed into solution architecture to avoid costly rework.

In the first instalment of this series, we examined the core principles of solution design. This article will zoom in on the design of medium and large system integration projects, and part three will discuss Agile design and its applicability in specific contexts.

Note 1 — In the remainder of this text, whenever we discuss solution design, it will be solely in the context of large integration projects. For core ideas and first principles, we recommend reading Part 1.

Note 2 — If the reader also requires some background in system integration or interface design, both integral topics to this discussion, we recommend you check the relevant articles.

2. FAQ

3. What Does This Series Cover?

This article is only one of 6 topics we want to cover in this discussion. Below is a list of the topics on the agenda:

4. Solution Design in Systems Integration

4.1 Definition

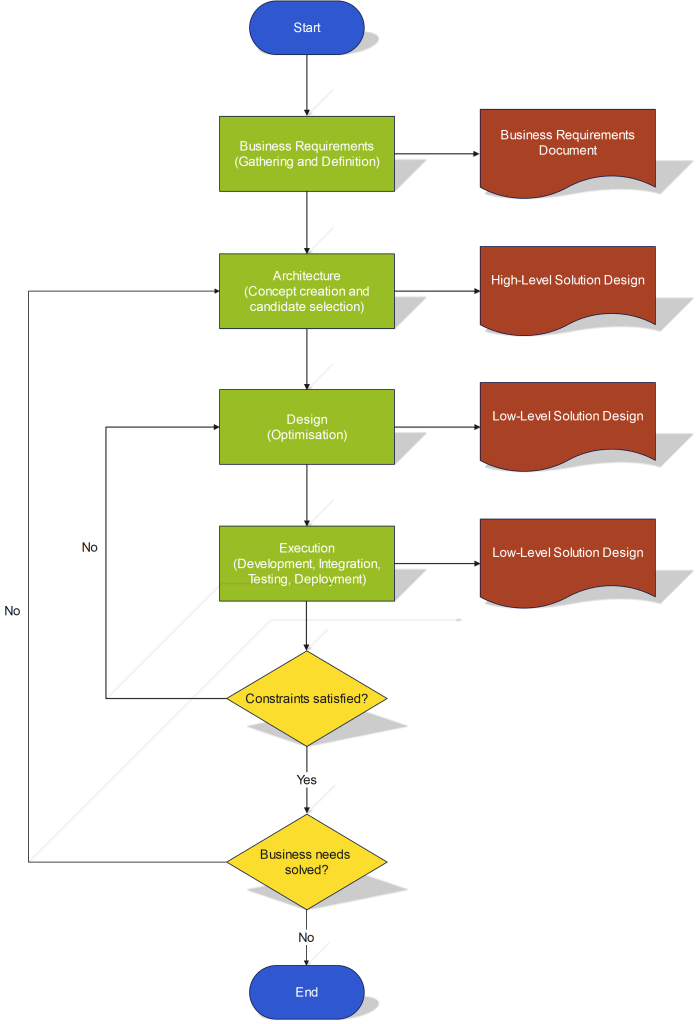

The story begins when the organization’s stakeholders acknowledge and decide to do something about a specific business need. At first, these needs are broadly defined; for example, designing and implementing an algorithm to predict the demand for umbrellas in the rainy season. During requirement gathering, typically conducted by Business Analysts, requirements are articulated and refined, and the results are documented in a BRD.

Requirement definition results in a clear set of objectives, some of which are functional, while others can be non-functional or project constraints. Non-functional requirements are fundamental to large software systems and will be discussed later in detail.

The stage is now set, and architects can construct the high-level design. Potential solutions are explored at a conceptual level during this stage, and a solution candidate is selected. After the high-level design is approved, tech leads and senior developers produce a low-level solution design in a series of iterations and revisions involving Business Analysts. Low-level technical decisions about the product and its use cases are made, and parameters are tweaked to satisfy its usability constraints.

Using the umbrella demand forecast application as an example, we can think of the high-level design decisions as follows:

Low-level technical design decisions might involve:

It is crucial to involve the customers in both design stages, and this involvement is especially vital in large projects where feedback loops can be very long. It may be too late and expensive to correct design problems after they have been heavily integrated into the more comprehensive solution and their effects propagated and mitigated in downstream applications. This process involving one high and another low-level design phase with many iterations in between them is the generic approach for solution design in system integration projects.

4.2 Exploring Many Designs

Executives at Toyota made it a requirement to consider a broad range of alternatives during the decision-making process. They even encouraged their engineers to seek feedback from specialists in different areas or departments for maximum diversification.

Toyota understood that although a full exploration of the design space can be costly and will inevitably delay product launches, this cost can be justified when the stakes are very high.

Toyota executives stress the importance of efficient implementations to compensate for the time spent deliberating on design decisions.

In software, alternatives often exist, and requirements for meeting deadlines may overshadow the viability of this exploration. This short-term tactical win is inefficient in the long term as it helps accumulate architectural and technical debt.

4.3 Solution Design Optimization

One of the outcomes of a solution architecture is a vector of design and operation parameters that can be combined and varied in different permutations.

Each combination will produce a slightly different design that behaves similarly at its core level but with slight variations in more peripheral areas.

One example of a design parameter is the number of TCP links between two components. One link is easy to manage, while multiple links make session and communication management slightly more complicated but increase throughput.

An operational parameter can be the information displayed on the dashboard of an infrastructure monitoring application. The amount of data can be increased for better sense-making of problems, albeit at the cost of additional data storage and processing.

We can think of this tuning process of design parameters as the optimization of an objective or cost function.

A generic and intuitive objective function is the utility-to-cost ratio, where we seek to maximize utility (business value) and minimize cost:

The complexity of the optimization process is because:

A sweet spot (or Pareto optimum) must be located. You know you have hit the Pareto optimum when no change in any parameter can be made without negatively impacting another.

There could exist not one but multiple Pareto optimums and part of the challenge is knowing which solution will work best.

Consider the above graph, where system availability and performance are plotted. The idea is as follows: increasing the throughput of a system also increases the risk of damaging it and putting it out of service. The 2D surface in the graph represents the set of Pareto optimums available.

You can decide which criterion is more important, performance or availability—an SLA placing system availability at 99.9%, for example, will determine the peak performance achievable.

Naturally, if you want to increase performance and availability simultaneously, you must upgrade your infrastructure at a further cost.

One method of preventing a deadlock is ranking design criteria by order of importance to stakeholders. We discuss this in the next section in more detail.

The optimization process, however, should produce a robust design vis-a-vis the criteria ranking. This robustness is vital as stakeholder influence and preferences change; you want to keep the same solution despite changes in opinions or choices.

4.4 Ranking Decision Criteria

In profit-seeking organizations, the top priority measure is long-term profit. Technical superiority is only desirable if it serves the business through competitive advantage, advancing the value proposition, or lowering long-term costs. Beyond that point, it is typically frowned upon by whoever is in charge of financials.

These subtle and conflicting constraints make technical choices non-trivial and subject to intense negotiations between business, technology, and finance departments.

Profit and utility aside, as long as the final product does the job, there is much room for maneuvering when fine-tuning design parameters. Consider the following example of an online and batch system in an ideal scenario.

| Attribute | Online System | Batch System |

|---|---|---|

| Profit | Non-negotiable | Non-negotiable |

| Utility, functionality, business value | Non-negotiable | Non-negotiable |

| Availability | A top priority in mission-critical systems | Medium priority as batch systems is required to be online only when needed. |

| Performance | High priority for the best user experience | Medium priority as long as the work is done within a reasonable time frame |

| Technology | Best in breed — it is more important to get optimal performance even at the cost of increased time-to-market | Mature technology that is easy to learn is OK if it delivers the required functionality. |

Power distribution in the organisation is often overlooked as an influential player in the decision criteria ranking game.

Key figures will impose their priorities, especially in a zero-sum game. A large part of a project’s success is guaranteed by securing long-term leadership support.

4.5 How Much Design Is Enough

You can explore the design space along two dimensions:

Ideally, you want to explore as many alternative designs as possible and perform as much decomposition and lower-level design as practicable. However, the exploration process might take a lot of time and resources if the system is large and complex and you typically want to operate within the allocated budget and timeframes.

So, how much exploration is enough? How much simulation or proof of concepts is sufficient before kicking off implementation?

The following excerpt from the NASA Systems Engineering Handbook provides some insights on the stopping criteria.

The depth of the design effort should be sufficient to allow analytical verification of the design to the requirements. The design should be feasible and credible when judged by a knowledgeable independent review team and should have sufficient depth to support cost modelling and operational assessment.

The design may also involve POCs and simulations, which are costly and time-consuming exercises. System architects and engineers must optimize their design efforts to achieve maximum fidelity at an acceptable cost.

If prototyping is not an option, expert intuition must be relied on at the cost of fidelity.

You also want to ensure that the selected candidate is also technically feasible.

Recommendations:

4.6 Solution vs Software Architecture

Several articles on this website have been dedicated to architecture, both software and solutions. In these short paragraphs, we will focus only on their relevance in the design of system integration projects.

One of the more straightforward definitions of architecture involves structures of connected nodes in a cluster.

The nodes are platforms, applications, or systems in the case of a solution, typically connected by interfaces. In contrast, in software architecture, the nodes can be classes or domains, and the connections are either structural or behavioural.

Where does the design come into the picture?

Architecture is a prerequisite for any further analysis or optimization. You usually choose how you want something to be done (architecting a solution), then design and implement its components.

5. When Does Solution Design Take Place

We have previously mentioned that solution designs come in two forms: low-level and high-level design. Each serves a different role and is prepared in a different phase of the software development life cycle (SDLC).

During the Analysis stage, a solution architect creates the project’s High-Level Solution Design (HLD). The HLD is an architectural plan for the IT system and is usually submitted alongside the Statement of Work (SOW).

The HLD is destined for a slightly technical but highly business audience, and its purpose is:

Once the SOW and HLD are signed off, and before any development starts, the Design phase kicks off, during which software engineers prepare the Low-Level Solution Design or LLD.

The aim of the Low-Level Solution Design is as follows:

6. Why Is Solution Design Important

Let’s start this discussion with a compelling anecdote illustrating how a massive gap can arise between a product implemented at a considerable cost and what the customers need.

6.1 Failure to Address a Business Need

In February 2008, Qantas – Australia’s national airline – cancelled Jetsmart, a $40 million parts management system implementation. The engineers simply refused to use it. The union’s Federal Secretary explained that the software was poorly designed and difficult to use and that engineers didn’t receive sufficient training.

The three reasons given by the union’s Federal Secretary to explain the abandonment of the project will be, as well as others, the subject of this section’s discussion.

We will argue that a proper design process should help eliminate such risks.

6.2 Avoiding Costly Redesign

Most would agree that the sooner an error is detected, the less costly it is to fix it—this means careful planning and design at the early stages of the project helps control uncertainty and project risk.

Rework is not an issue as long as it’s cheap, but such cases are generally rare. The price of rework can be measured by the cost of change and comes from the following:

When discussing rework or redesign, a distinction must be made between corrective measures and experimentation.

In the latter case, you typically carry more than one design and try these out (simulations, proof of concept) to test their feasibility and suitability. In the former, rework is created due to failure in the analysis or implementation stages, and this failure could have been avoided with more diligence.

Diligence in designing solutions can reduce or even eliminate rework.

6.3 Collaboration and Stakeholder Management

IT projects today involve a wide range of expertise from cross-functional departments such as business, security, compliance, infrastructure, procurement, and technology.

This complexity requires high levels of collaboration on, possibly, multiple projects running simultaneously.

Problems of efficient collaboration can threaten knowledge sharing, decision-making, planning and time management tasks in a large and complex social group.

They become more acute in the following situations:

Collaboration can be enhanced by channelling high-quality design information to all stakeholders.

Tools like JIRA, Confluence, and MS Sharepoint facilitate access, navigation, search, sharing, and collaboration on business or technical knowledge, immensely facilitating knowledge management across the organisation.

To mitigate any risk from misaligned requirements, schedules, timeframes, and priorities, solution design exercises bring relevant (and competing) stakeholders together (business/technology, client/vendor).

6.4 Reduces Project Risk

Following is a list of project risks that you can minimize through careful planning and design:

6.5 Getting Estimations Right

You can only effectively manage a project if you know how much it will cost and how long it will take to build. Consequently, effort estimation must be as accurate as possible, which is only realisable if you know exactly what steps, resources, and time are involved.

Effort estimation occurs at two levels.

Keeping the two levels of estimations in sync is not apparent, but that’s a topic for a different day.

With a detailed and comprehensive design, you can mitigate the optimism bias and avoid overlooking overhead tasks, of which the below list has some examples:

6.6 Designing Products for the Future

It is hard to predict the technical requirements of future IT solutions and how customer preferences will change.

What you can do, however, is:

7. Solution Design Requirements

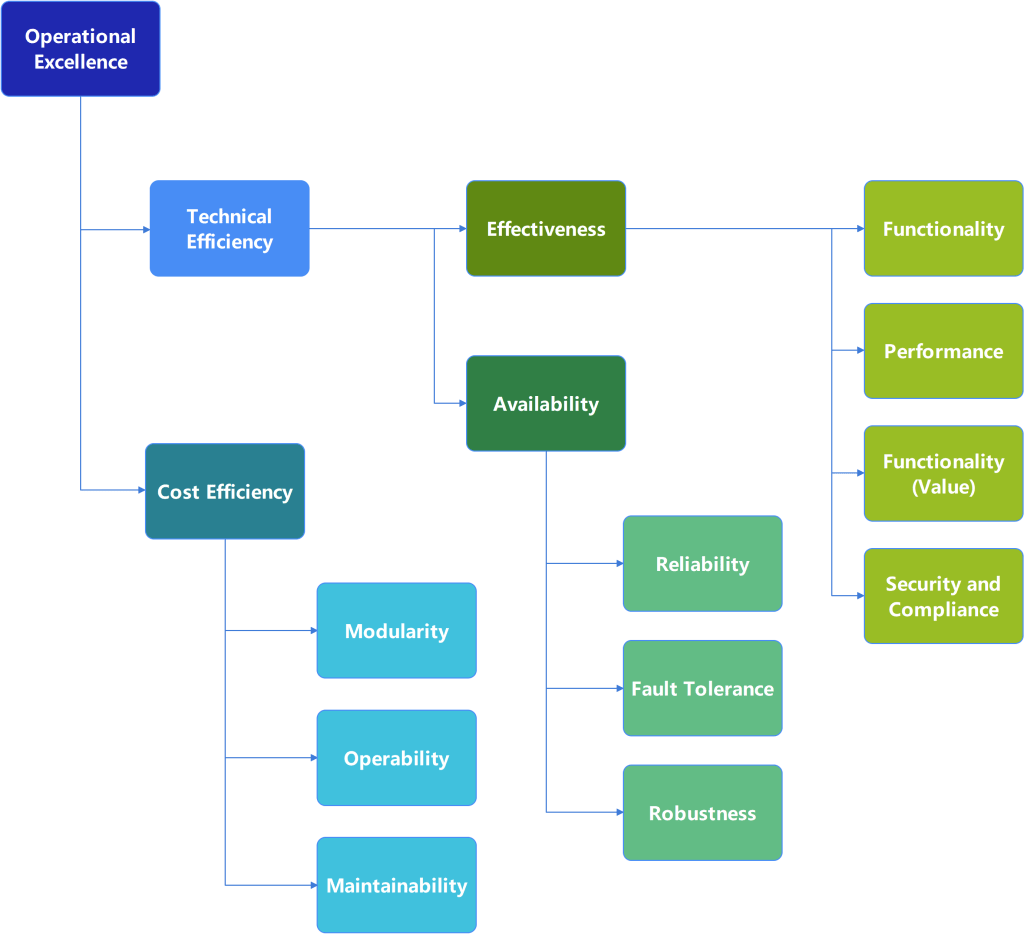

When designing a system, we look for an effective solution (does the job) that is also efficient (does it well) and cost-effective. The diagram below articulates these ideas with a hierarchy, with Operational Excellence (in the traditional sense, slightly different from what we use on their website for Software Development) at the top.

A practical solution can only achieve some things, and once the optimal design has been found, changes from there on would compromise one aspect for another.

The solution design process is an optimization exercise that selects values for key design and operating parameters to maximize an objective function such as utility/cost. The sometimes conflicting requirements from the above diagram make this process more art (through heuristics) than science.

Several design considerations exist, and a standard called ISO 25010 covering software quality has been published. The following sections will go through some of those in detail.

7.1 Functional Requirements

Functional requirements (also called business requirements) cover the following:

- Services and features that have business value to the user. They typically solve a business need.

- User experience, including user-friendliness, aesthetics, and running costs.

- The system’s behaviour in nominal and exceptional scenarios.

System users are generally happy to pay for the services they receive. For example, a video game’s functional requirements may cover the gaming experience, which OS systems it can run on, and the minimum hardware required.

7.2 Non-Functional Requirements

Non-functional requirements make the product viable and are equally interesting to the organisation and the end user.

The end user does not directly pay for non-functional requirements; the supplier does through initial investments and running costs.

Returning to our example of video game software, the typical gamer is not necessarily thrilled by the software’s technology stack, the CI/CD pipeline on which it gets built, or its maintainability and modularity as long as they have a great gaming experience.

However, maintainability and modularity are interesting for the vendor as they can keep costs down and increase the value proposition.

7.2.1 Compliance

Most industries, especially in the financial or health sectors, are regulated by public or private regulatory bodies.

For example, the payment industry has many regulations to follow. Most notable are EMV and PA:DSS set by global organizations such as Visa and Mastercard.

Sometimes, whole projects are implemented to comply with the latest compliance mandates.

Solution designs should observe rules and regulations for the industry, project, or software implemented.

7.2.2 Security

Software and cyber security requirements are essential to any IT project. See ISO 25010 standard on software quality for a complete list.

Security can be broken down into five major categories:

Security requirements must be observed in all designs involving sensitive information such as user and customer data.

7.2.3 Scalability

A system is scalable if it can be easily expanded (either vertically by adding more resources or horizontally by adding more nodes/instances) to accommodate additional load or higher performance requirements.

An example of a perfectly scalable system is a modern database engine like Oracle; it can be scaled horizontally (by adding more instances) and vertically (by adding more discs) without bringing down the service!

7.2.4 Modularity

Modularity helps to isolate functional elements of the system. One module may be debugged, improved, or extended with minimal personnel interaction or system discontinuity.

Extensibility and modularity are the hallmarks of great architecture and design.

Modularity is especially vital in mega-projects as it allows learning from mistakes without jeopardizing the entire project. With modular designs, systems can scale quickly and go into production as soon as the first unit is operational.

7.2.5 Fault Tolerance

Fault tolerance refers to the system’s ability to continue functioning even though one or more parts have failed.

Fault tolerance is critical in large system integration projects where many components collectively support a service; in such cases, the failure of one piece might knock the service out, and fallback mechanisms need to be implemented to prevent that.

7.2.6 Compatibility

Two systems are compatible if they can appropriately integrate and exchange data.

A different example of compatibility can be with OS platforms or hardware. An application is compatible with specific Operating Systems or platforms if it can be successfully deployed.

A good solution design does not limit itself to working only with specific software, hardware, or message types. Use industry-standard messaging and data transmission protocols to integrate with similar third-party systems.

8. Project Constraints

Project constraints serve as boundaries around requirements and are not the same. Given the requirements, an infinite number of designs can be put forward, with only a subset of which will be commercially viable.

You typically want to build a product or feature as quickly as possible to benefit from any windows of opportunity in the market. A specific budget also limits you.

Budgetary and schedule constraints are customarily encountered for most projects.

8.1 Cost-Effectiveness

Every project requires budgeting, and once the budget is allocated, it will not be easy to modify. For this reason, it is vital to have a very succinct idea of:

- How much effort is involved

- What type of skills and headcount are required

- If additional infrastructure or licenses are needed

- Any other project expenses

A solution design is a great place to tackle these questions. A cost-efficient design will also lower maintenance and operational costs.

8.2 Schedule and Timeline

Missing deadlines can mean a lot to a team. They can lose to the competition, incur fines from regulatory agencies, or send the wrong message to senior management.

The effort estimations generated from the solution design and the number of resources available for this specific project are usually what you need to get the dates right.

9. Conclusion

In Systems Engineering, you typically create an objective function representing the criteria your stakeholders care about.

The system design and operation parameters parameterize the objective function, and you would usually use Multi-Disciplinary Optimization (MDO) techniques to try and optimize that function.

Software engineering does not have the equivalent of an objective function. Instead, you have a set of requirements, some mandatory while others are optional, but it would be great to have them. This differentiation arises between the two disciplines and gives rise to two phenomena.

For these two reasons, solution and software design offer additional challenges that architects and engineers must tackle, and it’s never a good idea to sacrifice design efforts in an unsustainable manner.

Draw a line somewhere to guarantee minimal design efforts.

10. Further Reading

- Great talk by Martin Fowler on Agile Architecture.

- Fantastic lecture by Robert Martin on Clean Architecture.

- Design Definition and Multidisciplinary Optimization — MIT OpenCourseWare

Thanks alot for penning it

My pleasure!

Extremely well articulated. Provides a clear and concise understanding of fundamentals.

Thanks, Sunil; glad it was helpful.

This really compliments what I do and, going through it, opens my mind to space of thinking I needed to be in to deliver excellence, consistently.

Thanks